David Hockney’s art has always resonated with me—not just as a visual experience, but as a creative exploration of identity, perspective, and the power of seeing the world differently. We were both born in England and later moved to Los Angeles, which deepens my connection with him.

Yesterday I had the profound pleasure of visiting the David Hockney: Perspective Should Be Reversed exhibition at the Palm Springs Art Museum. It features nearly 200 of Hockney’s works, from his early sketches to his more recent innovative iPad drawings.

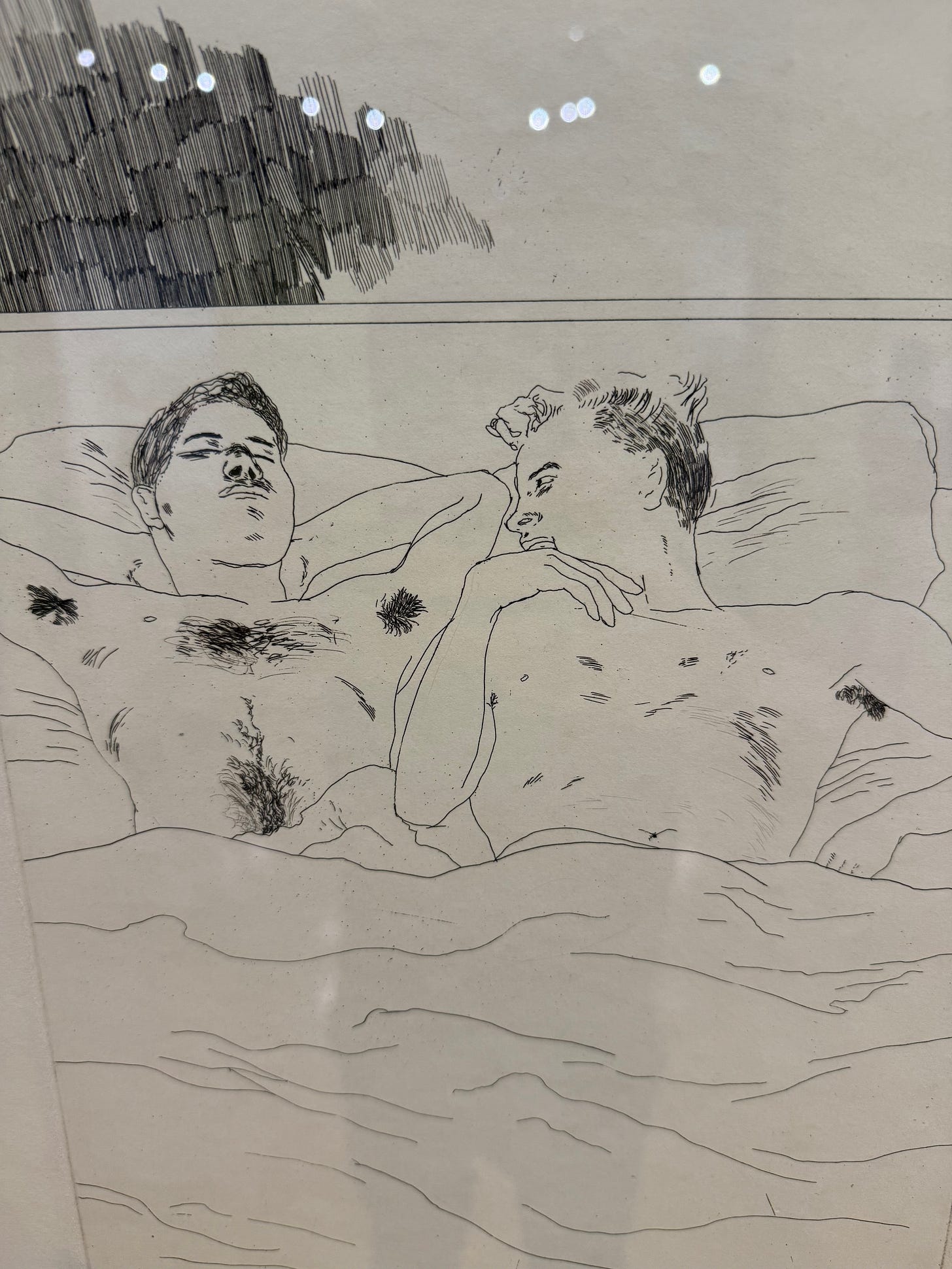

In his 1966 sketch, In the Dull Village, he portrays two men lying together in bed. This work is part of a series illustrating the poems of C.P. Cavafy, a Greek poet known for his candid explorations of love between men. Hockney’s ability to capture intimacy—without sensationalism, but with tenderness and truth—feels as radical and necessary today as it did in the 1960s. His unwavering representation of gay life and relationships during times of social repression has always been a source of creative inspiration for me.

Hockney’s work in the 1960s coincided with the era of playwright Joe Orton, whose darkly comedic plays—such as Entertaining Mr. Sloane and Loot—skewered British societal hypocrisy with sharp, subversive wit. Both Hockney and Orton challenged the status quo with their unfiltered and often shocking perspectives, through their respective mediums. The connection between these two artists is particularly meaningful to me, as I wrote my undergraduate dissertation on Joe Orton and his deconstruction of societal norms through his plays. Looking back, I realize that both he and Hockney shaped my understanding of how art can be a form of resistance—playful, provocative, and deeply personal all at once.

Hockney’s work in photography also reverses conventional perspective. In Photography is Dead. Long Live Painting (1995), Hockney juxtaposes a photograph of a real vase of sunflowers alongside a painted representation of the same subject. I love this piece, which explores the distinctions, intersections and limitations between the two mediums.

David Hockney’s embrace of the iPad exemplifies his lifelong fascination with technology and perspective. He began using the iPad as an artistic tool in 2010, shortly after Apple first released the device. Rather than viewing digital tools as a threat to traditional painting, he uses them as an extension of his creative process—allowing him to capture the landscapes of Yorkshire, England (where we was born) and Normandy, France (where he now lives) with immediacy, vibrant color, and a renewed sense of spontaneity.

Hockney’s endless curiosity, his refusal to see the world in only one way, is a personal inspiration and a reminder to me that perspective, much like identity, is never static. It evolves, it shifts, and expands in unexpected ways.

The current exhibition at the Palm Springs Art Museum runs through March 31st, 2025.

Beautifully written and articulated. It is enlightening to read your perspective given the cultural connections you share with Hockney. And your interpretation of the relationship between the works in the exhibit and the context they were developed in deepens my understanding overall of his passion and genius.